What was once considered exodus is now seen by those who remain, as endurance.

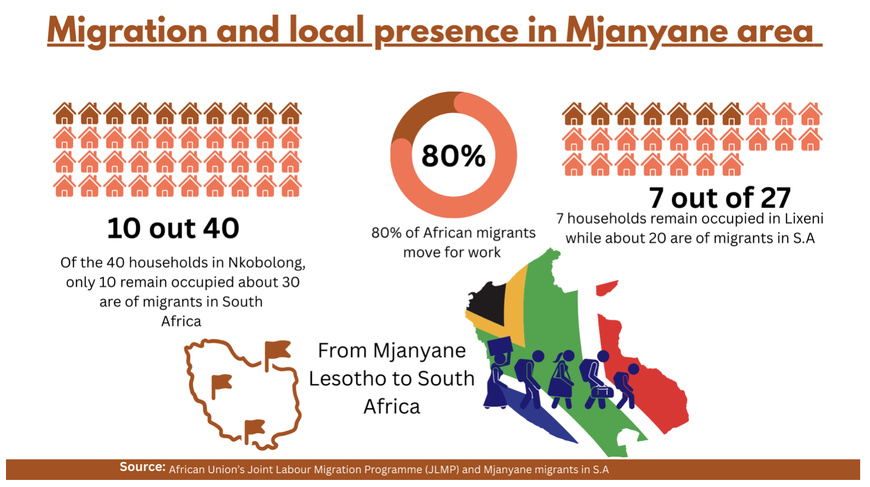

Across Southern Africa, migration is not a crisis; it is a strategy. According to the African Union’s Joint Labour Migration Programme, 80% of African migrants move for work. For Basotho in the border districts of Quthing, seeking livelihoods across the border is not abandonment; it’s an act of preservation.

In the farming town of Warden, South Africa, Mabuza Phoselo, originally from Nkobolong, stacks crates of produce with practiced ease. His brothers are in Cape Town. Their mother remains in Lesotho, tending the family home, alone but supported.

“I used to work as a shepherd,” he says. “The pay helped, but it wasn’t enough. In South Africa, I can meet our needs. I built a better house. I send money. We are doing more than surviving, we are progressing.”

Of the 40 households in Nkobolong, only 10 remain permanently occupied. The rest, more than 30, are shuttered but not abandoned. Their owners send remittances, fund school fees, and return for the holidays. They build brick homes with hard-earned money, decorate them with hope, and dream of retiring within them.

Lesotho and South Africa recently signed a 90-day visa exemption agreement, easing travel and protecting short-term mobility. For many migrants, it’s a lifeline.

“Before, overstaying was common,” Phoselo says. “Now we can visit home without fear.”

The change is rooted in the AU Protocol on Free Movement, which affirms the right of citizens to stay for up to 90 days in member countries. For migrants like Phoselo, it’s a step toward dignity.

“I believe in a future where jobs come back to Lesotho,” he says. “But until then, we’re doing what we can for our families.”

Mankosi Joel, a father from Lixeni, works on a farm in Queenstown, returning home only during Christmas. Still, his voice softens when he talks about home.

“If we had opportunities at home, factories, capital, I would come back tomorrow.”

He remembers telling stories to his children, watching their faces light up when he brings them new clothes each year. “That’s what keeps me going,” he says. “Their joy.”

Lixeni today is held together by 7 families who remain. More than 20 members of the village now live and work in South Africa, contributing to their home economies through informal businesses and remittances.

Across Southern Africa, migration is not a crisis; it is a strategy. According to the African Union’s Joint Labour Migration Programme, 80% of African migrants move for work. For Basotho in the border districts of Quthing, seeking livelihoods across the border is not abandonment; it’s an act of preservation.

In the farming town of Warden, South Africa, Mabuza Phoselo, originally from Nkobolong, stacks crates of produce with practiced ease. His brothers are in Cape Town. Their mother remains in Lesotho, tending the family home, alone but supported.

“I used to work as a shepherd,” he says. “The pay helped, but it wasn’t enough. In South Africa, I can meet our needs. I built a better house. I send money. We are doing more than surviving, we are progressing.”

Of the 40 households in Nkobolong, only 10 remain permanently occupied. The rest, more than 30, are shuttered but not abandoned. Their owners send remittances, fund school fees, and return for the holidays. They build brick homes with hard-earned money, decorate them with hope, and dream of retiring within them.

Lesotho and South Africa recently signed a 90-day visa exemption agreement, easing travel and protecting short-term mobility. For many migrants, it’s a lifeline.

“Before, overstaying was common,” Phoselo says. “Now we can visit home without fear.”

The change is rooted in the AU Protocol on Free Movement, which affirms the right of citizens to stay for up to 90 days in member countries. For migrants like Phoselo, it’s a step toward dignity.

“I believe in a future where jobs come back to Lesotho,” he says. “But until then, we’re doing what we can for our families.”

Mankosi Joel, a father from Lixeni, works on a farm in Queenstown, returning home only during Christmas. Still, his voice softens when he talks about home.

“If we had opportunities at home, factories, capital, I would come back tomorrow.”

He remembers telling stories to his children, watching their faces light up when he brings them new clothes each year. “That’s what keeps me going,” he says. “Their joy.”

Lixeni today is held together by 7 families who remain. More than 20 members of the village now live and work in South Africa, contributing to their home economies through informal businesses and remittances.

Manzolo Tyhali, a lifelong resident of Lixeni, tends to what remains. She remembers the old days: farming cooperatives, road repairs, rangeland management.

“We were self-sufficient. No one went to bed hungry.”

Now, she holds the fort with those who didn’t leave. The money sent from South Africa keeps shops running, schools open and food on the table.

“People here don’t even lock their doors. There is peace, trust. But we need work, processing plants for our aloe, wild peaches. If we had that, people would return.”

Mjanyane Community Councillor Nozakhele Bohlare believes there is a clear way forward, “Our people have experience in fruit farms and vineyards as they work in farms. If we invest in local agro-projects, they’ll come home and thrive.”

Chief Nokhanya Tyhali, who oversees Mjanyane, is pragmatic.

“Yes, villages are quieter. But people return. They invest. If Lesotho creates jobs, they’ll come home for good.”

Some houses are vacant; others are maintained by neighbours or through remittances. Still, youth are often left behind, sometimes vulnerable to harm.

Senior Superintendent ’Mamoipone Mohloai of the Lesotho Mounted Police Service doesn’t mince words, “Between January and June 2025, we had 23 sexual assault cases in Quthing. Eight involved children whose parents had migrated.”

She calls for intersectoral action, NGOs, health ministries and educators to support children left behind. “Migration brings opportunity, but it must not leave children exposed.”

Lerato Nelson Nkhetše, Director of the Migration Workers Association of Lesotho (MWA-Ls) urges action: “Migrant workers are essential, not illegal. But they face gaps in healthcare, documentation, and worker protections.”

He calls for bilateral agreements with South Africa and Lesotho-run mobile clinics to assist workers where they are. “They feed villages. They deserve safety.”

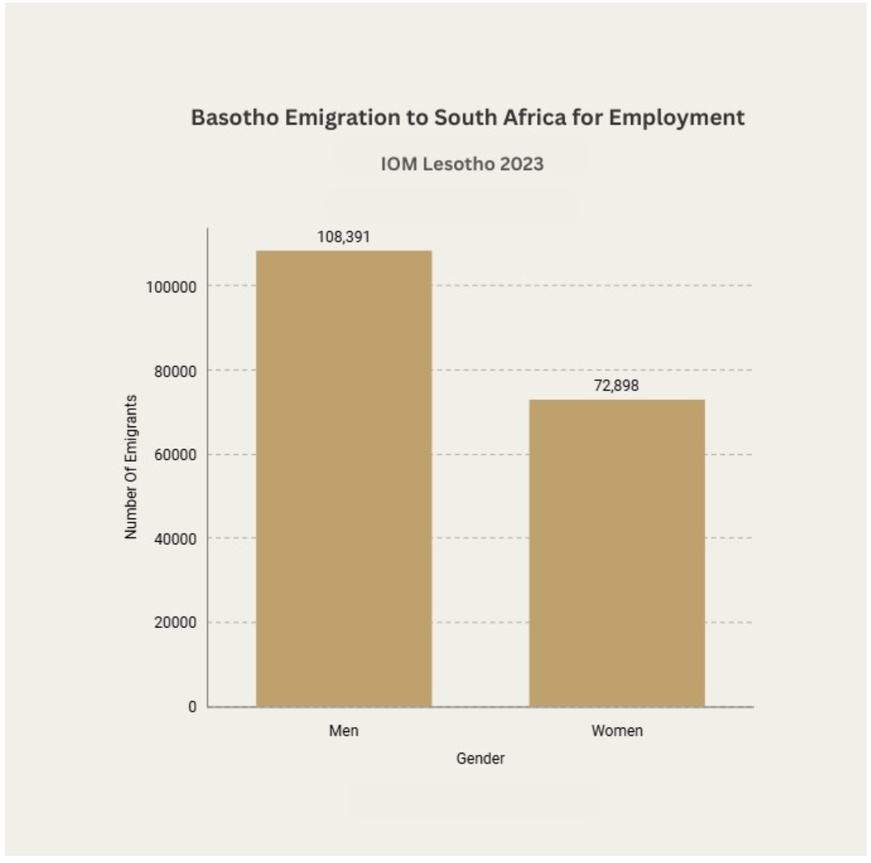

According to the 2023 report by IOM Lesotho, over 179,000 Basotho have emigrated: 108,391 men and 72,898 women to South Africa for employment.

Though migration to other countries exists, South Africa remains the epicentre of Lesotho’s labour diaspora. According to the 2023 report by IOM Lesotho, over 179,000 Basotho have emigrated: 108,391 men and 72,898 women to South Africa for employment.

“We were self-sufficient. No one went to bed hungry.”

Now, she holds the fort with those who didn’t leave. The money sent from South Africa keeps shops running, schools open and food on the table.

“People here don’t even lock their doors. There is peace, trust. But we need work, processing plants for our aloe, wild peaches. If we had that, people would return.”

Mjanyane Community Councillor Nozakhele Bohlare believes there is a clear way forward, “Our people have experience in fruit farms and vineyards as they work in farms. If we invest in local agro-projects, they’ll come home and thrive.”

Chief Nokhanya Tyhali, who oversees Mjanyane, is pragmatic.

“Yes, villages are quieter. But people return. They invest. If Lesotho creates jobs, they’ll come home for good.”

Some houses are vacant; others are maintained by neighbours or through remittances. Still, youth are often left behind, sometimes vulnerable to harm.

Senior Superintendent ’Mamoipone Mohloai of the Lesotho Mounted Police Service doesn’t mince words, “Between January and June 2025, we had 23 sexual assault cases in Quthing. Eight involved children whose parents had migrated.”

She calls for intersectoral action, NGOs, health ministries and educators to support children left behind. “Migration brings opportunity, but it must not leave children exposed.”

Lerato Nelson Nkhetše, Director of the Migration Workers Association of Lesotho (MWA-Ls) urges action: “Migrant workers are essential, not illegal. But they face gaps in healthcare, documentation, and worker protections.”

He calls for bilateral agreements with South Africa and Lesotho-run mobile clinics to assist workers where they are. “They feed villages. They deserve safety.”

According to the 2023 report by IOM Lesotho, over 179,000 Basotho have emigrated: 108,391 men and 72,898 women to South Africa for employment.

Though migration to other countries exists, South Africa remains the epicentre of Lesotho’s labour diaspora. According to the 2023 report by IOM Lesotho, over 179,000 Basotho have emigrated: 108,391 men and 72,898 women to South Africa for employment.

Lesotho’s Ministry of Home Affairs, represented by Public Relations Officer Marelebohile Elizabeth Mothibeli, has confirmed a new migration model in development with South Africa. The framework draws on study tours in Belgium and Namibia and aims to address long-standing documentation and labour issues.

“We’re building lasting solutions,” Mothibeli says.

The Mjanyane villages aren’t vanishing. They are evolving, sustained by resilience, transnational ties and a fierce commitment to family.

With policy reform, rural investment, and continental cooperation, Lesotho can harness migration as a tool for development, not just survival.

As the African Union’s Agenda 2063 reminds us, free movement isn’t just about crossing borders. It’s about building bridges across them.

“Our people don’t leave because they want to,” says Chief Tyhali. “They leave so they can return, with more than they left with.”

“We’re building lasting solutions,” Mothibeli says.

The Mjanyane villages aren’t vanishing. They are evolving, sustained by resilience, transnational ties and a fierce commitment to family.

With policy reform, rural investment, and continental cooperation, Lesotho can harness migration as a tool for development, not just survival.

As the African Union’s Agenda 2063 reminds us, free movement isn’t just about crossing borders. It’s about building bridges across them.

“Our people don’t leave because they want to,” says Chief Tyhali. “They leave so they can return, with more than they left with.”

Menu

Menu

They Leave to Uplift, Not to Escape: How Migration Sustains Lesotho’s Quiet Villages

They Leave to Uplift, Not to Escape: How Migration Sustains Lesotho’s Quiet Villages